Halldór Laxness’s Late Arrival

Halldór Laxness. Image sourced from The Reykjavík Grapevine.

Until recently, I had never even heard the name Halldór Laxness. This is embarrassing for at least two reasons. First, Laxness is a Nobel Prize winner, the first and only Icelander to receive that particular honor. Second, Laxness had a very prolific career, publishing more than twenty novels in addition to numerous short stories, plays, poems, travelogues, essays, and memoirs. Laxness also translated a handful of texts into Icelandic, including works by Ernest Hemingway, Voltaire, and his fellow countryman Gunnar Gunnarsson, who wrote primarily in Danish. Many of Laxness’s works have been translated into English, and many of those works have been celebrated and introduced by such illustrious writers such as Alice Munro, Jane Smiley, and Susan Sontag. Somehow I still missed the memo.

I therefore came to Laxness late, routed through a recent, growing interest in Scandinavian literature. This interest has largely been inspired by my own Norwegian heritage, though I’m certainly also subject to the wider cultural resurgence of interest in everything Scandinavian, from design aesthetics to socialist-leaning politics. (In fact, just the other night a new acquaintance invited me to join a book club for their “Nordic Summer,” the main event of which is to be a discussion of Laxness’s Independent People.) More than anything, though, I came to Laxness through the research I’ve been conducting in support of a new dance-theater piece I’m developing that draws on the medieval Scandinavian imaginary and its lineage of famed heroes. For months, I’ve been immersed in Saxon epics, Icelandic sagas, and more modern works by the likes of Henrik Ibsen, Knut Hamsun, Frans G. Bengtsson, and Karl Ove Knausgård. Throughout all of this research I’ve traced a genealogy of a culture’s thinking and rethinking of heroism.

It was only a matter of time, then, before I stumbled across Gerpla, a novel in which Laxness reimagines Icelandic sagas for the Cold War era. Gerpla appeared in 1952, just three years before Laxness would be awarded his Nobel. Six years went by before the novel received its first English translation at the hands of Katherine John, who titled her rendering The Happy Warriors. In an odd twist, however, John did not translate directly from the Icelandic-language text. As Magnus Magnusson reports, no translator could be found at the time to tackle the peculiarities of the original Icelandic. Therefore, John worked from a Swedish translation of Gerpla (though other commentators have said Danish). It would take another 60 years for Laxness’s idiosyncratic take on medieval Icelandic to be rendered directly from the source material, and thus for Gerpla to receive its due. For this reason, when Archipelago Books published Phillip Roughton’s new translation in 2016, more appropriately titled Wayward Heroes, it was as if Laxness’s novel had been translated into English for the first time — more than half a century after its initial appearance on the world-literary scene. A belated arrival indeed.

I find the novel’s belated appearance in English intriguing, and not only because I’ve been thinking a lot about what I’ve called belated reading (see “In Praise of Belated Reading,” from 23 July 2017). As it turns out, Wayward Heroes is intensely, and also ironically, preoccupied with its own belatedness. I mean this in a couple of senses. Most obviously, as a historical novel that revives the medieval Icelandic saga and its peculiar verbal and stylistic trappings, Wayward Heroes has a belated relationship to genre. As with the sagas of the famed Icelandic poet and historian, Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241), Laxness’s modern saga sets off at a brisk narrative pace, presenting the reader with a barrage of difficult names and allegiances to sort out. Wayward Heroes also drops readers into an unfamiliar and violent world, one with archaic norms for seeking justice and retribution.

But more significant than Laxness’s accomplished recreation of the medieval saga is his choice to revisit the saga genre in the first place. In themselves, sagas constitute a genre defined by belatedness. Sagas offer historical (or pseudo-historical) accounts of an age of heroes that had, at the time of composition, already passed. What scholars call the “Saga Age” refers to a period between roughly 850 and 1050, the 200-year period of violence and expansion that witnessed the development of Viking settlements in Iceland and Greenland. It is during this time period that most Icelandic sagas take place. However, it was not until the beginning of the twelfth century that the sagas began to be set down in writing. The advent of saga writing was, in turn, made possible by the large-scale conversion of Norsemen to Christianity, which had been set in motion a century before, starting around the year 1000. As the late scholar Robert Kellogg explains, “The introduction of ecclesiastical institutions into Norse culture — monasticism, literacy and the internationalist perspective of the church hierarchy — laid the foundation for a post-Viking educational system that was based on the reading of books.” Much like in the case of the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, which was written by a Christian poet reexamining his people’s recent pagan past, the sagas examine the Viking age from a post-Viking perspective.

Wayward Heroes takes the intrinsic belatedness of the saga genre even further. For one thing, Laxness appears to set his story at the end, if not after, the Saga Age. Indeed, in the world of the novel, the Icelandic settlement is firmly established, and most of the settlers there have already converted — or are considering conversion — to the Christian faith. For another thing, the narrator speaks from a perspective that is twice removed from the events he recounts. His is a third-hand account that he’s cobbled together from other written and oral sources:

Most of the stories of these warriors we find so remarkable that recalling them once more is certainly worth our time and attention, and thus we have spent long hours compiling into one narrative their achievements as related in numerous books. Foremost among these, we would be remiss not to name, is the Great Saga of the Sworn Brothers. Then there are the edifying accounts recorded on Icelandic parchments and stashed for centuries in collections abroad, besides the scores of old foreign tomes containing various well-informed, detailed reports, especially concerning later developments in our tale. . . . Finally, we have drawn from numerous obscure stories information that seems to us no less credible than the tales that people know better from books, it being our goal, in the volume that you hold now in your hands, to highlight the heroism of these two men.

Clearly, the narrator (or narrators; I’m not sure if the editorial “we” comes from Laxness or Roughton) is a much later historian, one whose project is part academic record-keeping and part misguided hagiography. The narrator’s reverent tone should already alert the reader to the irony of Laxness’s revival of the saga genre.

And this irony goes deep. Indeed, if saga writers like Sturluson provide belated accounts of heroes from a bygone heroic age, then Laxness offers a doubly belated account of wannabe heroes in a post-heroic age. The protagonists of Wayward Heroes are belated travelers in an already archaic world. Roughton indicates as much by making the surprising choice to retain the Icelandic spellings of the protagonists’ names: Þorgeir and Þormóður. Both names begin with a thorn — thorn being a letter (Þ, þ) that vanished from the English language in the fourteenth century, only to be replaced by the much less exotic digraph th. Although thorn remains a part of the modern Icelandic alphabet, Roughton capitalizes on the letter’s antiquatedness in English, where it is strongly associated with the runic flavor of Anglo-Saxon writing as well as the romantic Middle English of, say, Sir Gawayn and þe Grene Knyȝt. So, despite being “of” this ancient world, our intrepid heroes nevertheless stand out as being strangely superannuated within it, holdovers from a yet-more-ancient time.

Þorgeir and Þormóður’s doubly belated status is what drives the narrative of Wayward Heroes. Þorgeir in particular actively seeks opportunities to prove his mettle, having been raised on stories that marry valor with violence. For as long as he can remember, his father had regaled him with tales of his heroic exploits as a younger man, leading Þorgeir to believe him to “one of the greatest champions in the North.” (Unfortunately, Þorgeir not being the most perceptive of men, he fails to notice just how pathetically exaggerated his father’s tales are. Hence his surprise when his father dies an ignoble death at the hands of peasants: “Þorgeir Hávarsson was astonished at how easily his father died, despite his having fought berserkers in Denmark and brought fire and slaughter to Ireland.”) Following his father’s death, Þorgeir’s mother continues to nourish her son on valiant tales of Viking battles and sea voyages: “Þórelfur had little else to lavish on her son than tales of the prowess of champions of yore and paeans to kings who win the devotion of ambitious crofters’ sons with their bounteousness, rewarding stout hearts with weighty rings.”

Thus primed for heroism, Þorgeir enters the world with a literal axe to grind, spoiling for a fight. At the manly age of twelve, Þorgeir sets out from his uncle’sfarm to seek vengeance for his father’s death. Þorgils pleads with Þorgeir to stay and work, explaining that eye-for-an-eye-style retribution is a thing of the past: “Your mother is fully aware that the men of Borgarfjörður compensated your father’s slaying, to the satisfaction of all, long ago. . . . Nor do we have much heart for killing. The days are long past when men earned their keep through conflict.” Like his fellow farmers, Þorgils has little time for conflict or the uncertainty it brings. Þorgils also understands that a new era defined by Christianity is on the horizon — indeed, has already arrived. As far as he’s concerned, then, the Viking age is over, and Þorgeir’s heroism is thus both culturally and historically misplaced.

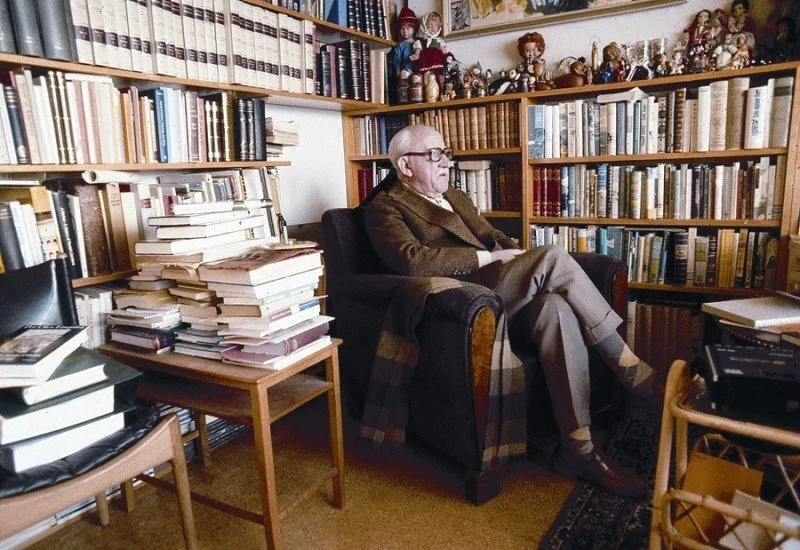

Laxness in his personal library. Image sourced from The Reykjavík Grapevine.

But for Laxness, it isn’t enough that Þorgeir and Þormóður cling to old-fashioned ideals. No: Laxness goes after the ideals themselves. In particular, he exposes history as a fiction written not by winners, as the adage typically goes, but by a host of lagging travelers who stumble late onto the scene. In Wayward Heroes, the perception of heroism is literally an effect of a belated arrival. On one of their early adventures, for instance, Þorgeir and Þormóður ride ahead of their company and come upon a man with a load of wood on his back, struggling against the wind on the far side of a river. Þorgeir calls out to the man, but the stranger offers no response. Furious at being ignored, Þorgeir urges his horse across the river and drives a spear into the man’s chest. A gruesome scene ensues:

The man, sorely wounded, fell beneath his burden. He clutched at his chest and groaned. Þorgeir leapt from his horse and started hacking at the man’s neck to take his head off, though the task went incredibly slowly due to the dullness of his weapon, despite the champion’s firm intent. Finally, however, the head came off its trunk, and the man lay there dead on the ground in two pieces, his bundle of brushwood next to him.

The morbid comedy of Þorgeir’s unnecessary violence immediately gets amplified, when his faithful retinue arrives and, from the gory fallout, infers a heroic feat that never took place:

At that moment, their fellow travelers from Reykjahólar arrived. They declared this a great deed, done by a true hero. On a hill a short distance away stood a little farm. . . . The group rode to the farm and announced the slaying, saying that the hero with the stoutest heart in the Vestfirðir had come. As everywhere else, the folk there marveled at how dauntless a man Þorgeir Hávarsson was.

Elsewhere in Wayward Heroes, Laxness ironizes the historical view in other ways, principally by revealing poets to be habitual exaggerators, if not outright liars. Consider the episode where Þorgeir encounters a skald (or poet) composing a lay titled “Glory of London”:

Þorgeir could make out that the lay was in praise of the greatest of all of King Thorkell the Tall’s many outstanding exploits: his victory over the English, when he sacked London and endeared himself to King Æthelred, after first ravaging Canterbury. The lay named that battle as the seventy-first that Thorkell had fought, and the most glorious. It told of how hundreds fell to the blue battle-mattocks of Thorkell’s warriors in a single hour of the morning — neither eagle nor she-wolf went hungry that day.

Þorgeir, who was present for the battle in London, well knows that the event would be better described as a rout than a sacking. “[You] prate about us having bravely conquered London,” Þorgeir tells the skald, “yet you know better than anyone that in London, piss and pitch were poured on us, and we were sliced with table knives like cured shark, and those who did these deeds were women and decrepit, helpless old men.” In his turn, the skald schools Þorgeir on the political realities of poetizing:

It goes ever for kings as for vicious dogs: they lie on their spines when their bellies are scratched. That is the lot of skalds. . . . Nothing is dearer to any king’s man than verses exalting his sovereign, to feel the praise poured on his king drip onto him. Every warrior loves hearing afterwards of how bravely he comported himself in battle, no matter how frightened he actually was, or how useless his king really was — or, no less, if he had been drenched with piss.

History is written to flatter those in power, regardless of whether or not they are, strictly speaking, winners. In disabusing Þorgeir of his naïve views on historical truth, the skald also casts doubt on the saga genre as a whole.

Thus, the tragedy of Þorgeir and his companion Þormóður (himself a skald) is twofold. Not only are they both historically belated in terms of their Viking values, but they also lack the ability to historicize those values. That is, they fail to understand how the very stories they long to emulate and reenact are belated constructions that actively mythologize the past. Ultimately, the sworn brothers’ pursuit of an already outmoded heroic status leads them to untimely and ignoble ends, the details of which I leave the reader to discover for him or herself.

Portrait of Laxness painted by Einar Hákonarson in 1984. Image sourced from Wikipedia.

But what does all of this mean? What is Laxness getting at with his complexly ironic saga that undermines its own historical — and thus also its own literary — foundations?

To my mind, all of Laxness’s irony about belatedness and the upholding of long-dead ideals seems to caution against the kind of forgetting that occurs when we cling to stories of the past without properly examining them. In an earlier novel, The Atom Station (Atómtöðin, 1948), Laxness’s protagonist comes from a rural place where the sagas constitute the bulk of cultural life. In this novel, the sagas represent a uniquely Icelandic inheritance, one that is under threat from American military occupation of the island as well as from international pressure for Iceland to join NATO. In Wayward Heroes, by contrast, the saga takes on a different significance. Here, Laxness seems to gaze straight into the complex and dark heart of his own literary and cultural heritage. This heritage no longer provides rustic comfort in relation to the arrogance, selfishness, and snobbery of modern Reykjavík. Instead, it warns against the dangers of historical naïveté. No doubt this was a pressing concern for Laxness following the horrors of WWII and the during anxiety-driven fervor of the Cold War, under which conditions he penned his modern saga.

In Wayward Heroes, then, Laxness shows his keen awareness that the idiot violence of the Viking past continues to haunt the present. Heroic consciousness remains alive and well today, showing itself in ever-more-nuanced, ever-more-twisted manifestations. We’ve just been late to calling it what it is.

Works Cited

Laxness, Halldór. The Atom Station. Translated by Magnus Magnusson. Methuen & Co., 1961.

———. The Happy Warriors. Translated by Katherine John. Methuen & Co., 1952.

———. Independent People. Translated by J. A. Thompson. Vintage, 1997.

———. Wayward Heroes. Translated by Phillip Roughton. Archipelago Books, 2016.

Magnusson, Magnus. “The Fish Can Sing: Translation and Reception of Halldór Laxness in the UK and USA.” Scandinavica, vol. 42, no. 1, May 2003, pp. 13–28.